- Home

- Oksana Marafioti

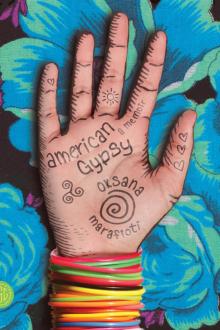

American Gypsy Page 6

American Gypsy Read online

Page 6

The first time Dad auditioned him, everybody grew quiet and the people rehearsing nearby drew closer to listen.

“He’s a wunderkind,” Dad exclaimed later while Mom attempted to shorten the sleeves of his magenta stage coat with my father still in it. “It’s like fire shooting out of his fingertips.”

“That’s all the boy thinks about,” Mom said. “Not healthy. And now he’s dropped out of school! Again!” Ruslan had dropped out at the age of nine to beg on the streets, per his mother’s instructions. He went back, but struggled through every day.

“He’s not good at academics, but with fingers like his, who needs algebra?”

“He should have other interests, kick a soccer ball once in a while.”

When I was nine and Ruslan twelve, Grandpa Andrei ordered Kristina to leave. She had a habit of stealing husbands or, more often, borrowing them for a night. Ruslan’s father was a mystery many band members often and without shame bet money to solve. Kristina was also a heroin addict and Ruslan often suffered the rage that came with the high.

When Ruslan’s mother left, she didn’t say goodbye. He himself showed no emotion as he watched her get into the taxi from the hotel window. He had decided to stay with the troupe.

Later I found him sitting on a ratty yellow couch down in the hotel lobby with his guitar case propped against the wall. He was softly tapping a rhythm with the heels of his scruffy shoes. I couldn’t tell if he was going to cry or rip the couch in two, so I sat down on the other end, hoping he’d do neither with me there.

“The next show’s in three hours,” I said.

He scrutinized the people walking about as if he’d never seen anything more interesting.

“You just gonna wait here this whole time?”

“Don’t feel sorry for me,” he said.

But how could I not? If my mother had up and left, I would’ve been terrified.

“I’m not,” I said, so nervous he’d grow silent again. “We’ll take care of you.”

He stopped tapping.

“Oh yeah?”

“Sure.” I shrugged. “Now we’re your family.” But I wanted to say “I’m your family.” One day I was a nine-year-old with the musings of a nine-year-old, the next I’d sit through two shows to see him play for a minute or two. Over the next four years Journal Number 1 grew fat with love notes:

Before going onstage last night, Ruslan winked at me. I will die if he does it again. God, please, make him!

Ruslan showed me more dance steps today. I lost count. Twice. And walked out even though he didn’t laugh at me. Now I’m stuck in this hotel room, too embarrassed to show my face.

I have to go back to Moscow in a week, and he won’t even notice how I love him.

Six months after my thirteenth birthday, during our tour of Uzbekistan, Ruslan asked if I wanted to tag along to buy guitar strings at the music shop a few blocks away in downtown Tashkent.

“On the way,” he said, “there’s something I need to ask you.”

At the shop, the bushy-sideburned salesman peered at us like a toy terrier after a bath. “Young people these days. Barely weaned and already doing God knows what. Running around together, unchaperoned. Aren’t you a little too young to be out with this fella? How old are you?”

“Thirteen,” I said.

“Young man?”

Ruslan jabbed a finger at the packets of strings that hung on a hook above a poster of Lenin preaching to a sea of soldiers. “Two of those. If you’re not too busy.”

“Vonuchie Tzigane (rotten Gypsies).” The old man plucked the packets off the hook and tossed them in a paper bag. “But such are the times. Let everyone do as they please.”

I couldn’t understand it. Our clothes were good quality, our faces clean. We paid with rubles and displayed good manners. How could a stranger tell us apart from everyone else?

On the way back to the hotel, Ruslan squeezed the brown bag into a ball, and I nearly had to run after him. We passed a park where a small gathering of old men were arguing over a game of chess. The sidewalks bustled. We tried to shoulder our way through a crowd boarding a trolley, each passenger fighting for their rightful place.

“Are you all right?” Ruslan asked. He took my hand so we wouldn’t get separated.

“Are you?”

A sharp nod, and he pulled me to the other side of the street.

“He’s old,” I said. “He didn’t mean it.”

“You notice how it’s never just ‘Gypsy’? It’s always ‘dirty’ or ‘rotten’ or ‘stupid.’ They mean it, Oksana, never doubt that. And the old are most dangerous. You can’t change their thinking.”

“Nothing we can do about it,” I said.

“In Romania, right now, Romani our age are fighting back.”

I’d heard of rallies going on in Romania at the time. Romani all over Europe told stories about women being sterilized without consent; there were rumors that no Romanian Gypsy could get documents in order to work. Some of the younger Gypsies were becoming restless.

“As soon as I save up enough money I’m going to join them,” he said.

“In Romania?”

“Important things are happening there.”

“But we need you here, too. Probably even more.”

He laughed. “Yeah, the show would fall apart without me.”

I found the entire conversation terrifying.

“Funny how the old man thought we were dating,” he said.

“Hilarious,” I said. “Do you want to?”

He cleared his throat and his ears flushed. “Want to what?”

“We can go to the movies together sometimes. I mean, do you like me that way?”

How could I have said those things? He was practically my brother. Uncle Stepan had taken him in, treated him as his own son. Mortified, I couldn’t wait to get to the hotel room, where I’d lock myself in the bathroom and drown in the toilet.

“It’s okay,” I said. “We’re really good friends and—”

He stopped, curls of his shiny black hair caught in the wind.

“Okay,” he said.

“Good. I only said that because I don’t like going alone.”

“Do you want to go steady with me?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Thank you.”

“No problem.”

* * *

In Mom’s eyes, Ruslan’s lineage made him unacceptable, and Dad would never allow his daughter to associate with a moneyless dropout except during performances. Ruslan was as close to a leper as a young Rom got.

The night Dad caught me and Ruslan backstage, our heads bent over a pamphlet on the Romani equal rights movement in Romania, Dad chased him around the entire theater.

“The boy is a bastard!” he later said behind the closed door of our hotel room.

I remember wishing for the building to cave in before the entire band heard my father’s voice in the hallways. Mom was making beef stew on a single burner that she wasn’t supposed to have.

She shook a serving spoon at me. “There’s bad blood in that family tree. What kind of future does he have? No money, no way to take care of a wife—”

“Wife? We were reading,” I said. In truth, I was reading. Ruslan had asked me to help him practice his reading and writing, and I said yes before he was even done. It amazed me that he couldn’t string together the simplest of sentences on the page. He jumbled syllables and words, and knocked the books away in frustration. Dyslexia was something neither of us considered, since we’d never heard of it, but I’ve wondered since why none of his teachers had caught the signs.

“His own mother didn’t know who knocked her up,” Dad said. “No decent woman will want him.”

“It doesn’t matter. He’s too old for me anyway.”

“See? You’re thinking about it, but beware, my daughter. If I catch that govnyuk (shithead) anywhere near you, I’ll rip his head off.”

I knew that by “rip his head off ,” Dad mean

t “He’ll be fired and on the streets.”

Six months later I turned fourteen. We were back in Moscow, the band on a three-month hiatus. I was so afraid that Ruslan would lose his job that I made certain Dad had no reason to fire him. Instead of going to the movies, we wrote love letters. Zhanna took Ruslan’s dictations and carried the contraband between us like a partisan dodging unfriendly fire.

The night Ruslan came to talk, Zhanna and I were staying at Esmeralda’s flat. He wouldn’t come in but had asked Zhanna to fetch me.

The landing was dark, with only the elevator buttons blinking on the wall. When I saw him, I knew something I wouldn’t like was about to transpire. He wore a suit with a black tie over a white shirt. Roma boys dressed like that for official matters ranging from weddings to gang disputes. He was also carrying a briefcase. Next to him I felt distinctly unofficial in my bathrobe and slippers.

“I missed you,” he said. That’s how he started every letter: I miss you. I want to embrace you. I want to be near you. Every sentence started with “I” and ended with “you.” Without much fuss, the letters evolved into declarations and promises made by both of us and intended to be kept.

“You look handsome in that suit,” I said. “I love you.”

“And I love you. It’s one of Stepan’s.”

He balanced the briefcase on one raised knee and clicked it open.

“I brought something for you,” he said, pulling out a thin strand of a necklace. “It’s not very expensive but it’s silver. I figured if I give you a ring, your dad will send you to a convent and I’ll never find you.”

“Very funny. You came here in your suit to give me a present?” My voice betrayed the edges of worry. “I don’t want presents. Come in for tea.”

“I have three hundred rubles saved up from the tour—”

I pulled the robe tighter around my neck, my fingers stiff like twigs.

“I have to do this, Oksana. When I come back I’m quitting the band. Maybe get a part-time gig at the Teatr Romen.”

I was seriously considering wrapping myself around him, hanging there until he missed his flight. I wanted to beg and to scratch my face, to scare him into staying.

“Romania is so far from here. The letters will take very long,” I said.

“Will you wait for me?”

Placing the briefcase on the floor, he walked over and draped the necklace around my neck. Then he kissed my cheeks. The tip of my nose. My fingers came alive. I seized the collar of his jacket, not out of passion but to keep him from leaving. He kissed my chin. Then lips, burning his mouth to mine.

“When we’re husband and wife,” he said, “we’ll kiss every morning, after breakfast, at noon, midday nap, and many times in the evening.”

“Stepan won’t let you go alone.” But I knew that at seventeen Ruslan was perfectly able to travel unsupervised.

He looked at his watch and pushed the elevator button. “I’m off. As soon as I get to Bucharest I’ll call.”

The elevator heard my pleas and refused to budge from floor twelve, but Ruslan was onto us, and turned to take the stairs. I was still holding on, barring his way.

“Please, Ruslanchik. Please. When I’m sixteen we’ll go together. Just wait two years.”

He kept entreating me gently to let go. He had so much to do in Romania. If anyone heard that his girlfriend made him stay they’d laugh at him. He’d be gone for only a couple of months. On the ground floor he pried away my hands and kissed them while apologizing for hurting me.

“That’s fine,” I called out to his receding back. “Romania can have you and your promises.”

But two weeks later, I was planning our wedding. Sure, I’d refuse at first. After what the bastard did, he’d have to drag his knees for days in front of me, begging forgiveness. I’d act nonchalant, perhaps go visit Grandma Rose in Armenia for a couple of months before saying yes. I already knew my parents wouldn’t approve of our plans. We’d have to wait until my sixteenth birthday, but no matter. More time for me to drive him crazy, make him see that he’d made the wrong choice by picking a country over me.

A month later I began to worry. No letter had reached me. Had the politics seduced him, leaving no time to jot a quick note? I could ask around, but I’d go to Hell before hounding for information like an obsessed girlfriend.

I didn’t have to. Instead, Hell came to me.

* * *

My parents were celebrating a good friend’s birthday. Ivan had been a band member for years and was like a brother to my father, who believed that anyone who’d back him up in a fistfight against five angry crane operators was family. Esmeralda had arrived earlier to help Mom make solianka, a spiced soup. She had brought Zhanna along—a great idea, since my parents threw parties on a weekly basis—and once the talk of work turned to politics, I was inevitably ordered out of the room to watch Roxy.

At one end of the table Roxy and I were listening to Zhanna tell a story about an abandoned church outside Leningrad inside of which people claimed to have heard a woman crying.

“I heard it on TV today,” she said, dipping a chunk of rye bread into the soup. “A man peeped through the boarded-up window, and you’ll never believe what he saw.”

Seven-year-old Roxy covered her ears. “Don’t tell it if it’s gonna be scary.”

“Well?” I urged.

“A flying apparition of Mother Mary!”

I lowered Roxy’s hands. “What a fairy tale. Mother Mary’s flying about like she has nothing better to do.”

“I’m telling you, it was on the news,” Zhanna said. “Now people are going to camp out around the place. I bet all of Russia will be there soon.”

“Won’t she get tired of flying?” Roxy said.

I was going to add something smart-ass when a conversation between Ivan and Dad caught my attention.

“Stepan is coming back with the body day after tomorrow. What a tragedy.”

“I had no idea.” Dad pushed aside his bowl. “How did it happen?”

“How do you think? They caught him alone, beat him, dumped him in the alley. It’s not like the cops are eager to volunteer information.”

The din around the table softened.

“What’s this?” Mom said.

“Stepan’s boy was killed yesterday,” Dad said.

Ivan had only the skeleton of the story. After one particularly explosive demonstration, Ruslan and a few local Romani got caught up in a fight with some gadjee boys. No one knew who instigated the fight, but it ended with the participants scattering to escape the police. Later Ruslan was found dead behind the local pet clinic. He’d been beaten to death.

Mom’s hand flew to her mouth, but Esmeralda and Zhanna were already sobbing as if someone had turned on a switch.

Ivan’s hands lay clasped on the white tablecloth as he attempted to answer all the questions. Being the bearer of bad news was never a good thing for the bearer.

Zhanna hugged me and her sobs filled my ears. But I had no tears of my own. I felt like I’d been given a drug that was slowly pulling me under. I propped up my elbows on the table, rested my chin in my hands, and thought, If I faint right now and my face lands in my mother’s solianka, could I drown in it before anyone reaches me?

* * *

I refused to go to the funeral.

“I don’t believe you,” Zhanna said to this. “Where’s your soul? I thought you loved him.”

My parents had had one of those fights that left holes in our kitchen walls, so I was staying at Esmeralda’s for a couple of days, and Roxy was at Grandma Ksenia’s. Earlier Esmeralda had gone to meet with Stepan to arrange the three-day vigil. She was also in charge of the music (Romani often hired small bands to escort funeral processions into the cemetery).

“Go to the vigil at least. We’ll go together after midnight. Stepan’s not even staying home tonight, but he’s leaving it unlocked for visitors.”

I leaned on the windowsill, stories above the kids playing dodge

ball in the yard, where spring blew kisses from tree to tree.

“No,” I said.

“Are you being such a bitch just to piss me off or what?”

“You got it. All this is for your benefit.”

After several very long minutes I felt Zhanna’s arms wrap around me. She rested her chin on my shoulder.

“You can cry if you want.”

“I am,” I said.

That night I told Zhanna I was going home—it wouldn’t do to have her think she had swayed me. Since Stepan’s place was an hour away by metro, I took a taxi. As a rule I’d never get into a car driven by a man with a barely healed gash on the side of his face, but I honestly didn’t care if anything happened to me. Nothing compared to what had happened already.

Inside Stepan’s flat, the living-room furniture had been pushed against the walls. There were candles burning in large sconces, the only source of light. Normally I enjoyed the scent of candles, but that night their sinister spitting made the air too thick. From my spot in the living-room doorway I dragged my eyes to the coffin in the middle, raised up on a platform. It was dark brown with fake-silk lining that looked like frothed icing.

I came near Ruslan. So close, I saw the details of his suit, the red carnation peeking out of his breast pocket, the spattering of hairs on his knuckles, and the makeup someone had tried to cover his bruises with. They had combed Ruslan’s curls straight down the sides of his head. He looked like a choirboy ready for “Ave Maria.” I unwound the scarf from around my neck and wiped down the side of one cheek, and continued until his face came alive with color, the bruises almost black in the candlelight. I never expected that the last time I’d see him would be like the first, his body marked by violence.

It was the strangest sensation to sit the night through in the presence of my first love’s death, and yet I remember so little. At my great-aunt Ophelia’s funeral, relatives threw themselves across her coffin and screeched at the sky for God to love her. A Romani funeral is never a shy affair. It’s meant to celebrate a life lived and secure a smooth passing between two worlds. I’d heard in some countries that the Romani lay their loved ones in tombs furnished with their most precious belongings, and others bury them standing or sitting, a sign of ultimate liberty from life’s oppressions. For Ruslan, songs would be sung, Christian prayers recited, and tears would flow for the next forty days, the time it takes for a soul to depart from earth. Pominki, memorial meals, on the ninth day and the fortieth, would ensure his safe passage.

American Gypsy

American Gypsy