- Home

- Oksana Marafioti

American Gypsy Page 3

American Gypsy Read online

Page 3

Once Aunt Varvara actually opened the door and thrust a plastic bag at me. “Here,” she said. “I don’t want anything of your alcgolichka (alcoholic) mother’s in my house.”

I obediently brought the bag home. When Mom opened it, I saw the silver coffee set she had given Aunt as a gift upon our arrival. She had to pay the customs officer a nice sum for letting it pass the gate. Mom stuffed the set back in the bag, hands shaking. “Take it back and tell her it was a gift.”

I did, three more times: a reluctant messenger caught between two emotionally charged alphas.

“I said I don’t want it.” Aunt Varvara’s slitted eyes narrowed at me. She took up most of the love seat. Cousin Aida came into the room and somehow managed to squeeze in next to her mother. Aida used to read during her meals. Growing up, I thought it was a sign of great wisdom. That day, I felt sure that she’d talk sense into both our mothers. Then she put on her best foo dog grimace, and I blanched.

Aunt ordered for me to sit down and folded her meaty arms across her meatier chest.

“We have allowed you into our home, found you a place to live, done everything to make you comfortable. Tell me, why is your mother so ungrateful? Does she think just because she’s family it’s okay to bring her problems here?”

Her words froze my insides. “What are you talking about?”

“Don’t act stupid, Oksana. I shouldn’t be surprised, now, should I? That’s what your mother gets for marrying a Gypsy. Did you know we had to keep him secret from our friends? For years! She didn’t really believe they would have a normal life together, did she? Arsen was right not to want you people here in America, with us. He warned me you’d be trouble.”

A cold weight pressed down at my heart. Had my father been right about Uncle Arsen intentionally leaving out the most important document in the visa application? Aunt Varvara went on. “They thought because they lived in Moscow, and because they were artists”—this last she spit out like bad tobacco—“that made them better than us. But because your mother knew all these important people didn’t make her better than us. We actually had to work for a living!”

“But you never worked,” I almost pointed out, then decided this was unwise.

“I told Arsen not to send that visa. I knew you’d be a burden, an embarrassment! We can barely make it here as it is without more people to take care of.”

Aida, my cousin, my friend from childhood, and the one person I believed to be unshakably good, said, “Grandmother took such good care of you half-breeds when your spoiled parents went off on their tours. She made sure you got the best caviar and the biggest birthday parties. But we are her grandkids, too.” Her eyes shot resentment. “Didn’t we deserve caviar, Oksana?”

Grandma Rose, a matriarch of my mother’s family, had risen above poverty after being orphaned at the age of three and became a successful accountant. She had made one great mistake in her life: she had allowed her kids to think she owed them something. Every time one of them found themselves in trouble, Grandma came to their rescue. With time, they grew to expect it.

If it were up to Grandpa Andrei, my dad’s father and the manager of the troupe, kids would never be permitted on the long tours that took the performers all over the fifteen republics; but most of the performers had no one to leave the kids with, and Grandpa grudgingly gave in only when he had to. For this reason, Mom sometimes had me stay with Grandma Rose in the small Armenian town of Kirovakan.

I remember only one birthday party from my entire childhood. I was turning five and Grandma had made me a dress with an orange-pink satin bodice and a tulle tutu so huge I couldn’t see my feet over its starched skirt. It made me look like a blooming marigold. I remember the barbecue fires infusing the air with the aroma of grilled beef and lamb, tables creaking under the weight of food: trays of horovatz (barbecue), pickled vegetables, dolma with garlic sauce, crusty matnakash (bread), crystal bowls full of walnuts and raisins, and sweet rolls called gatah. A crowd of guests, including my aunts and uncles and cousins, lifted their wineglasses to my health and happiness, and Armenian music rose and fell in a rhythmical lilt of duduk (Armenian oboe) and drums. And I clearly remember twirling around the dance floor until my head spun. I love my grandmother for that memory.

Years later, when I retold the events of that horrible day at Aunt Varvara’s to her, Grandma Rose laughed, her plump middle shaking, and said, “For goodness’ sake! I fed you so much caviar because your optometrist had said it would help with your vision problems.” I was born with a condition that rendered my left eye nearly blind. The doctor had thought that caviar and carrots could remedy that, and although I loved eating both, that eye, to this day, is there only for decorative purposes.

Now, when I replay that scene at Uncle’s, I come up with all the right things to say, but back then, I just stuttered.

Only when I stepped into the blinding sunlight did I allow myself to cry. By the time I took the steps up to our apartment, I had a migraine and my nose ran like an open faucet.

Mom met me at the door, her eyes searching for the bag of silver. “Did she keep it this time?”

“I threw it away in an alley.”

“Gospodi (my God), Oksana! That set was nearly two hundred years old. What…” She saw my face. “You look sick. What’s the matter?”

Mom held me while I tried to tell her what happened.

Although Uncle and Aunt never openly admitted that they didn’t want us in America, they did try, indirectly at least, to stop us from coming. Was the Gypsy side of us so unbearable that they would find any reason to dismiss us with such ease? At fifteen, I assumed that was it, even while it confused me. For the longest time I tried to solve the riddle of that day’s events, but I’m no Indiana Jones. One day I gave up.

It was the last time I knocked on my aunt and uncle’s door.

SURVIVING AMERICA

We didn’t own much furniture: a rickety kitchen table with chairs, two cots, and two small couches Uncle had bought for us from a furniture warehouse downtown. At first I’d thought he did it out of guilt, but then I learned Mom had to pay him back as soon as she could.

Our father had disappeared, and all Roxy and I knew was that he’d gone to Russia for something our mother avoided discussing but cursed about whenever she vacuumed the couch cushions.

“That’s why he wanted to come to America so bad,” she’d say. “Used me, used my brother. Babnik (skirt chaser) arranging his own fresh start, is he now? Shtob on provalilsya (May the earth swallow him up). Shtob on sgorel (May he burn). Shtob on sdokh (May he drop dead)!”

I was glad Mom had her cushions to vacuum, and the floor-to-ceiling living-room window to keep washing, and the fridge decorated with Roxy’s drawings to clean out daily. I was glad, because all the activity kept her from blurting out the truth about Dad that I wasn’t ready to hear.

Often in those first few weeks, I felt an unsettling tug of nostalgia—for Dad and, incredibly, for Russia. I’d started a journal, using one of the two graph-paper notebooks Mom had brought over. On its cover I wrote “Journal Number 2”; I’d left the first one with my Romani cousin Zhanna, daughter of my dad’s sister back in Moscow, imprisoned at the bottom of her dresser until I decided what to do with it. It contained the old life, and I wasn’t sure how much of it I wanted to bring over.

Zhanna was the only person I trusted not to read it because she’d lived most of the events mentioned in its pages along with me. We were the same age and spent a lot of time together during concert tours.

Once we boarded the train to Estonia in the middle of the night, twenty-five of Grandfather’s musicians and their families stuffed canned-food-style into the last three cars. When the ticket agent at the Moscow central station found she was dealing with Gypsies, all the good tickets mysteriously sold out. We were stuck riding in the back, where everything swerved and rattled and swayed from side to side like a shark’s tail.

Inside our private car I fell asleep to the mechanica

l heartbeat under my ear. Say what you will, but a train is an insomniac’s paradise. You can complain about the drafts and the sheets with stains as old as the Kremlin, but once your head hits that pillow, the train song reaches for you.

The only reason I woke up early the next morning was Zhanna’s voice outside our compartment door. On the bunk above, my father snored in harmony with the train, and Mom was already up and making her rounds. As the band’s administrator, she was a mother hen to twenty-five fully grown adults.

I slid open the door.

“And then you cut up the goat balls and add them to the salad,” Zhanna was saying.

“Is that so?” The conductor was a woman shaped like a barrel with two sacks of flour hanging off the front. She stood with her hands behind her back and did her best to sound nice, but I could tell she was ready to find Zhanna’s parents and lecture them on how to raise a proper little girl.

“Yes,” Zhanna continued, and nodded to me for support. Her golden hair gleamed in the sunlight. “But you have to make sure they’re fresh, not shrivelly. That’d be disgusting.” She made a face.

“Little girl. Your language is inappropriate and you shouldn’t make up such stories.”

“But I’m not, am I, Oksana? Don’t our parents make goat-ball salad all the time?”

At eight years old I was looking into the mischievous eyes of a best friend. I puckered my brows at the barrel woman.

“All the time. Goat, sheep, even ferret balls.” The conductor cringed. “They’re a delicacy all over the world. Even in Italy.”

In a Russian’s eyes, especially a Russian woman’s, Italians are gods. “Girls, you are horrible … But really?”

We nodded in unison.

“How do the Italians eat them?”

Zhanna’s expression was innocent, clean of doubt, even though her mom had stepped out of their compartment and seconds remained before she came to investigate and we got punished for the rest of the tour. “With spaghetti sauce, of course.”

The pain of missing my cousin was so tangible I felt like I could quite possibly extract it with tweezers, like a splinter of glass, had I been able to reach that deep inside myself. To ease the longing, I figured I should create a list of things I missed about Russia and then one of everything I didn’t. Lack of sanitary napkins and tampons, for example. (We used to have to wrap gauze around bulky wads of cotton, which was responsible for a number of bloodstained skirts and pants. Also, it made you walk like you’d spent one too many days in the saddle.)

Me, Aunt Laura, and Zhanna in Moscow, 1988

I never thought I’d be homesick for a place I had been eager to leave, but the oddest things went into the “missed” column: the soothing glow from the rose-patterned lampshades of our Moscow living room, and the irritable cat we left behind, named after Michael Jackson. I missed the mashed potatoes Dad used to make, the ones I refused to eat because of the lumps, and the way my mother’s Climat perfume lingered in our house for hours after she’d left for a business meeting. Surprisingly, I also missed the snow. Blended with the scent of the freshly cut fir trees huddled behind FOR SALE signs near metro stations, the snow smelled like Christmas.

Moscow snow, though, reminded me bitterly of my first school fight. A month after Aleksey Moruskin pinned the Gyp sign to my back, he sidled up during the sixth-grade school party and asked me to dance.

“No,” I said, suspicious of his motives.

Nastya saw the exchange and rolled toward us, knocking people aside like a bowling ball.

“You Gypsy skunk,” she shouted. “Why don’t you go back to begging with your folks at the train station instead of stealing our boys?”

“Don’t call me that.”

“What? Gypsy or skunk?”

“Say it again and you’ll be sorry,” I said.

“Let’s see you try.”

We made arrangements to meet behind the school in ten minutes. Like a duelist with star power, Nastya brought an entourage of six girls. I waited alone, the winter night biting my skin. Nastya and I stood ten feet apart, our breathing already uneven. The girls cheered louder and, spurred by their enthusiasm, Nastya and I rushed at each other. She slapped my face, and the pain bit harder than the cold. I wished she’d used her fist, because that seemed less degrading. The girls’ voices flocked into the black sky. Nastya landed another one on my face, and then, as if possessed, I roared and punched her in the middle of the chest. She fell in the snow, gulping for air.

The girls circled their friend, helping her stand as she pressed her hands to her breast. Panic rounded her features into a caricature of herself.

I took a step closer, my ears loud with the beginnings of hysteria. I didn’t want Nastya to die.

“Get her!” someone screamed.

I tore across the field behind the school, sinking deeper in the snow with each step and my lungs burning hot. When I finally crossed the field, I sprinted home, but they caught up before I rounded the last corner.

One of them yanked me back by my coat and shoved me forward face-first onto the ice-covered sidewalk. I rolled over and lay there stunned, surrounded by my classmates.

“Well?” Nastya said, peering at me. “Did you girls see how she almost snatched Aleksey as soon as I wasn’t looking? That’s what Gypsy whores do, because they start having sex at like ten and then they can’t stop.”

“My mom said they grow boobs and curly hairs faster than normal people,” one of the others volunteered.

Nastya leaned down. “Not so fast now, are you?”

“You can have your fat Aleksey,” I spit out, rising as the cold from the ground fizzed into my bones. The night grew darker, even the streetlamps seeming to fade.

“She’s bleeding!”

They were gone as the blood crept down my face and over my eyes.

At home, Mom pressed bandages soaked in hydrogen peroxide to the cut several inches above my hairline while Dad demanded to know what happened.

“I fell down,” I said.

“You were walking and suddenly fell down?”

“Leave her alone,” Mom said. “Be useful and fetch that chocolate bar from the fridge.” She had read in a scientific journal that eating chocolate helped the body produce more blood.

“Are you out of your mind, woman? She’s going to have a scar. I want to know how she fell down, that’s what I want to know.”

Mom dabbed iodine around the cut, and I leaned my head into her hands, a bit dizzy.

“We should call the ambulance?” Dad hovered, trying unsuccessfully to make me talk, but I was afraid that the truth would drive him to Nastya’s parents’ doorstep. Dad had experienced his share of racial confrontations, which usually ended with something straight out of Romeo and Juliet, with his cousins and friends going after the offender, who in turn recruited his own family to battle the mad Gypsies.

I hadn’t missed my family’s frequent thespian adventures, and like an old woman I now wanted only peace and a certain amount of predictability.

* * *

I wasn’t the only one adjusting. My newly single mother moved about the apartment with restlessness and unease. Still, she laughed and joked with us, and made sure to cook our favorite meals, like the eggs over easy with tomato slices for breakfast, or pelmeni, Siberian dumplings, for dinner. Only sometimes did I glimpse the pain living behind her eyes.

Since we didn’t have a TV, a clock radio served as entertainment.

“Is that Eagles?” Mom exclaimed if a good song came on. “Ooh, turn it up. That’s a great song. ‘Velkom too khotelle Caaaaalifornya. Soshalovah playz, soshalovah playz.’”

“Mama. Those aren’t the words,” I’d tell her. “It’s ‘such a lovap ace, such a lovap ace.’”

“Oh, what do you know? I performed this onstage millions of times.” And she’d continue singing in her scratchy alto as she filed her nails or put away the dishes while I rolled my eyes at her horrifying accent, relieved that no one but Roxy and I were arou

nd to hear it.

Mom had indeed sung that song before, though probably in even worse English. When my parents toured the Soviet Union back in the seventies and eighties, their repertoire had consisted largely of Soviet and Romani songs. Everything else, especially American music, had been banned from concert halls ever since I could remember. But my parents and a couple of the younger ensemble members shared a passion for rock and roll, and managed to sneak away to gig the underground clubs, where the managers took bribes in exchange for silence.

Only a year before, Dad had attempted to jot down the lyrics of “Dancing Queen.” In the kitchen of our Moscow house, he stopped the tape and rewound a single line over and over until he could somewhat decipher the words screeching out of his boom box. As neither of my parents spoke English then, the lyrics they performed were usually a nonsensical jumble. But the public loved it anyway and sang along with enthusiasm.

Youkondanz. Youkonjyiy

Haveeng ze tyne ofur lie

Ooh see zegyol, watchatseen

Diging ze donseekveen

There was the ever present risk of someone ratting the place out to the officials; the possibility created an atmosphere of nervous excitement. Perhaps that was why Soviets drank as if celebrating their last day of freedom.

I remember watching from a table in the back on many occasions, my parents crammed on a tiny stage of some dive along with the drummer, the bassist, and the equipment. The musicians regularly complained about everything: the location, the acoustics, especially about the drunks who climbed onto the stage in an attempt to grab Mom’s mike and sing along. But they always found more illicit places to play.

Dad and the other guys wore wing-collared polyester shirts and bell-bottom pants, giving the eighties the finger. They played as if there were no audience, tweaking their sound during songs and making appreciative signs at one another by tossing their manes whenever a particularly juicy chord change occurred. But Mom had more fashion sense: her custom-made dresses were enhanced with patterns of sequins she’d carefully sewn on herself. And she had more people sense, too. When she sang, each person believed she sang for them. There was always at least one lush who’d ask Mom to run away with him or to marry him, and she’d let him know that she was flattered but that she’d done both already and no, thank you, but please you must come see another show.

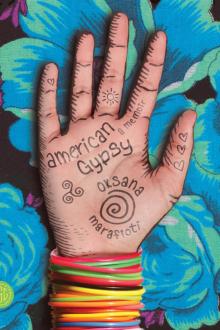

American Gypsy

American Gypsy